The Meaning of Low-Intervention Winemaking

Walk the aisles of a chain supermarket and you get a quick education on how the American food complex works. There are brand names that we trust and have consumed since childhood – Rice Krispies, Heinz ketchup, Best Food mayonnaise – and each aisle is chock full of examples. These are products that come from companies that produce food items on a mass scale, large enough to fill demand nationwide in the world’s largest economy. They are also made from formulas, so that every time you purchase them, they taste exactly the same.

Most of these products have been engineered to hit the pleasure center of the brain. Fast food restaurants have been perfecting this craft for years. They engineer their food to contain what your brain craves, to make it irresistible – a perfect combination of fat, salt, sweetness, and flavor – which makes you go back for those fast food french fries time and time again.

“I met her in a club down in old Soho, where we drink Champagne and it tastes just like Coca Cola” – The Kinks

Not so with wine, or at least that is what I was raised to believe. My father taught me to know the nuances between not only between grape varieties, but also between, say, a Pinot Noir from Burgundy versus one from California. He taught me that wine was the only beverage that made a statement of place – it showed the character of the location where it was grown. And not only that, every vintage was different, too, due to weather conditions during the year.

From this perspective, wine is infinitely difficult to sell on a supermarket shelf. Yet there are countless brands that have become as mainstay in chain supermarkets as Hostess Twinkies. So what gives?

“Variety’s the spice of life, that gives it all its flavor” – William Cowper

What it boils down to is that there are winemaking tricks that can be used to make wine taste exactly the same year in and year out. (There is a reason why many winemakers in the business get winemaking degrees at accredited universities, so that they can learn all the tricks of the trade, just like fast food engineers). And what is in that bag of tricks? The US allows over 60 additives in wine, from benign ingredients such as tartaric acid (a natural acid already in grapes) to velcorin or mega purple, which are, um, not so good. And even worse? Manufacturers of alcoholic beverages are not required to list ingredients on their labels. I believe that this does a huge disservice to wine consumers.

Low-intervention winemaking has become a buzzword with the smaller producers who do not make formula-based wines. What it means is that these wines contain little to no additives – and likely are far less likely to give you a headache. Lumen has followed low-intervention practices since the start, and now we have taken it to the next level – by controlling the farming practices to produce the gapes that go into our wines. We grow organic, and employ the same careful practices with our wines. We want you to know that the real deal is in your glass: healthy, chemical-free, and with a true statement of place.

-Will Henry

Here is a link to a great article about the most common additives in wine – check it out (and just so you know, we don’t use any of them, except for a low dose of sulfites prior to bottling).

Is wine good for you?

The pendulum always swings when it comes to what foods and beverages are good for your health. I remember in the 70’s we were told that fat was bad, and along with that came cheese, avocados, butter, and bacon. Oh, the horror. People switched to margarine. I remember tubs of that processed hydrogenated vegetable oil taking up valuable space on the shelves of our fridge. (My father threw his body in front of the train when it came to cheese, but that’s another story. “It’s health food!” he would exclaim.)

If my father were alive to see the latest trend of alcohol-free beverages kicking wine off the grocery store shelves, he would be horrified. Wine was as much a part of our family dinners as were utensils on the table. My parents considered it the perfect complement to food, and despite the alcohol it contained, a healthy beverage – when taken in moderation. And yes, there were studies that backed this up. The Mediterranean diet was all the rage, and it included a couple of glasses of wine a day. The Europeans were living longer, with less obesity and heart disease, than their American counterparts, and they were also consuming a lot more wine.

“I cook with wine. Sometimes I even add it to the food.” – W.C. Fields

In my early 20’s I began to look closely at my diet due to some health issues. Not a single item went into my shopping cart without me reading the list of ingredients. I remember at the time that I had taken a liking to Mike’s Hard Lemonade (don’t judge, I was young and White Claw wasn’t around yet). I was shocked when I turned the bottle around and couldn’t find an ingredient list. What was in this stuff? And furthermore, why was breakfast cereal required to list ingredients and health information, and this mystery beverage not? The answer lies in government regulation. Food products are regulated by the FDA while alcohol is controlled by the TTB. The TTB has no label requirements for ingredients. They require manufacturers to list alcohol content, a sulfite warning, and little else. The Surgeon General recently made a suggestion that alcoholic beverages should also carry a cancer warning on the labels, much like cigarettes. I can hear my father screaming from the sky about this one.

“Penicillin cures, but wine makes people happy.” – Alexander Fleming

Many studies have shown that there are health benefits to wine that is consumed in moderation. Furthermore, not all wines are created equal. Large-scale, supermarket brands tend to make their wine more like Coca Cola. It’s a formula. They want it to taste the same every time you pull a cork (or twist a screw cap), regardless of vineyard source or vintage. The TTB allows up to 75 chemicals that wineries are allowed to add to their wines, with no requirements to list them on the label. I can only imagine how many of these chemicals are in the bestselling big brands.

The lesson to be learned from this is that healthier (and more honest) wines usually come from the small producers, who are looking to make a wine according to its traditional, natural process of fermenting grapes with yeast, aging in oak barrels, and adding a small amount of sulfur prior to bottling for stability and freshness; like we have always done at Lumen. And starting in 2024, all of our wines labels will come with a list of ingredients, so you know exactly what you are drinking. “Wine is health food!” My father also liked to exclaim, and in our case, he was right.

-Will Henry

If you didn’t notice the rows of vines as you approached our vineyards this year, you would be convinced that you had happened upon a snail farm. At picking time, it was inevitable that hundreds of them wound up in the picking bins, and we hunched over the bins as we always do, picking out leaves and stems, and this time around, a myriad of gastropods.

What can I say about organic farming? Sometimes certain critters decide that they are in the right place, and we just have to deal with it. The growing season was unusually cold and damp, with very few heat waves, and the snails found a happy home. Who am I to disturb their pleasant, albeit slow, progress across the canopy?

In ancient Greece, snails represented fertility and the fruition of hard work. The Aztecs refer to snails as representing cycles of the universe and reincarnation. Japanese culture considers snails the most fertile of beings and the gods of water, while across the African continent, snails take on a variety of meanings from symbols of the creation of man to eternal life.

As has become happenstance with this strange vineyard, the experts all said that they had never seen this before. When I mentioned it to one of my workers, he shrugged his shoulders, “I have never heard of snails becoming a problem in a vineyard.” As the year progressed and the snails became ever more plentiful, I decided to take it as a good omen, much like the Greeks, the Aztecs, Africans, or the Japanese. A bountiful harvest will be mine, I told myself.

For the most part, that was what occurred. The fruit was healthy and in balance, and if we were forced to put a bit more work into sorting snails out of the fruit bins, so be it. The vineyard workers all joked if I was going to make a sopa de caracol (snail soup, a delicacy in Latin America, although they make it with conch). Just wine, I retorted, although perhaps we would call it Wild King Pinot Noir, Escargot Block.

– Will Henry

In this episode of The Reluctant Somm, Will Henry of Lumen Wines shares his full-circle journey through the wine world. He discusses his innovative approach to natural wines with sulfite alternatives, his and his wife’s restaurant, Pico, in Los Alamos, and his collaboration with the esteemed Lane Tanner. Tune in to hear about the unique experiences that have shaped his career, including a memorable story about the legendary Randall Graham. Join us for an insightful conversation that weaves together wine, food, and fascinating industry stories.

The 2021 harvest was near. I called my winemaking partner, Lane Tanner, and asked her to find as many neutral oak barrels as we could gather – we had to accommodate extra fruit coming in. The quality in this new, mysterious vineyard was just too good to pass up.

I dubbed the vineyard ‘The Wild King,’ after seeing what it produced after being allowed to grow, unfettered, unpruned, and unwatered, for more than a year.

There was more fruit hanging than we could handle in our little winery, so I threw some feelers out to a few of my winemaker friends; to see if anyone was interested in getting some last-minute Pinot Noir at a bargain price. Every single one of those winemaker friends, after they came to look at the fruit in person, said yes. Ryan Roark, Gavin Chanin, Jessica Gasca, Mike Roth, and Ernst Storm were all on that lucky list. The most memorable visit of that bunch was with Gavin.

“This just turns everything we think we know about viticulture on its head,” he exclaimed excitedly. “We spend all of this money on the best vineyard management practices, year after year, and then we come across fruit like this that came from doing nothing. It blows my mind.”

The challenge, as I saw it, was how to maintain the vineyard going forward. If I continued to leave it unpruned, eventually the vines would overgrow the rows (maybe within a year), and the vineyard would become basically unmanageable. You already could not drive a tractor down the rows, which means it would be nearly impossible to carry out normal practices such as composting, mowing or weed control. Even hand-harvesting would become completely impractical at some point.

The reaction from every one of the vineyard experts that I queried was a whole lot of pondering and head-scratching. Not one of them had ever heard of a successful vineyard practice that excluded pruning. They all recommended pruning during the coming winter and going back to a more conventional farming method.

At home one night I explained to my wife, Kali, that I had to figure out a different way forward. “I don’t want to go back to normal,” I said, “I want this vineyard to produce fruit like this again.” I wondered aloud who I might call on who could think outside the box.

And then it came to me: Randall Grahm.

For those of you who don’t know Randall, a brief history. Randall graduated from UC Davis in 1979 with a degree in Plant Sciences, where as he states it, he developed a “single-minded obsession with Pinot Noir.” He purchased a property in Bonny Doon, a neighborhood in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and planted vineyards. His wines, produced under the Bonny Doon label, were hugely influential on the burgeoning California wine business. Randall was an early adopter of biodynamic practices, and earned the nickname the ‘Rhone Ranger,’ having been largely responsible for the introduction of Rhone varieties to the American public. I have known Randall loosely for many years (my father was a co-conspirator, and a huge fan, in times past), and I figured there was no better person to ask to think outside the box than he.

Randall in his happy place, the vineyard. Popelouchum, 2021

Randall arrived on a cool August day and I toured him around our young plantings, then took him down the hill to see the wild vines. We walked the rows together while he looked curiously at the small bunches and plucked berries off the vine and popped them into his mouth, spitting seeds at pace with his steps. “Remarkable,” he said, more than once. After many long minutes, I explained my conundrum. He smiled.

“What you have here,” he said, “is the classic battle between winemaker and winegrower. One wants quality and the other quantity. The trick is to find the balance where one can make a great wine, and still make money growing the fruit.”

I agreed, but expressed that it still did not answer my question: what should I do with this vineyard going forward, and even more importantly, next year? I guess I was hoping to get some definitive answer from the guru, as though he had the answers to one of the wine world’s greatest puzzles. He was quiet for some time, and then started to offer some suggestions. His greatest piece of advice was to not to be afraid to experiment. He also suggested I connect with a few other people in the industry that were pursuing alternative vineyard practices, and he gave me some names.

We took Randall to dinner at our restaurant, Pico, and had a wonderful meal, punctuated by much wine philosophy and many ‘Randallisms.’ After Randall said his goodbyes, I didn’t feel much closer to an answer, but woke up the next morning with the semblance of a plan.

I decided to divide the Wild King Vineyard into blocks, and experiment with each block in a different way. One section would be pruned traditionally the coming winter, while another block would be allowed to continue another year of wild growth. I would also experiment with watering. Some sections of the vineyard would be watered on a regular schedule, while others would not be watered at all – to simulate the way that the vineyard was farmed the prior year, and to see which, if not all, of the techniques were what made the most difference. One way or another I am determined: to again produce the magically wild fruit that we came upon in 2021.

Next up: The Wild King Ascends into Madness

– Will Henry

I was always a believer that being wild was a good thing – to a point.

Be it a confrontation with a bear on a remote surf trip in British Columbia in January, or a night spent adrift on the open ocean in a boat that had lost its engine, wild is exciting, invigorating, and makes us feel that much more alive. Unless, of course, it gets so wild that it puts our lives in true jeopardy. There is often a fine line.

I never thought that I would have the opportunity to draw this line of comparison with viticulture, but then again, life offers many interesting twists and turns. In the summer of 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, we were planting a new vineyard in the Santa Maria Valley – the Warner Henry Vineyard – named after my late father. My attention was entirely focused on what is to become our first estate vineyard, tending the young vines and making sure they became healthy adults, and learning to become a farmer day by day. But just down the hill from this new vineyard, a new chapter was unfolding – one which would teach me much more about farming than I had bargained for.

The workers commented one day that there was a vineyard on the way up the hill that had not been pruned the year prior, and bud break had just occurred, meaning that the time for pruning had come and gone. Vineyards are pruned for many reasons, most importantly because it allows for farming practices to occur more easily, and promotes vine health, vigor, fruit production, and vineyard longevity. Leaving a vineyard unpruned is a big no-no in standard agricultural practices, because it can lead to many more problems down the road. The workers asked if I knew what was going on with that vineyard, but I did not. The owners are my neighbors, but I had never met them – and while I had not seen anyone working the vines for quite some time, I was focused on my own baby vines.

Fast forward a few months, and I was driving up our road, and noticed that this wild vineyard was holding a lot of fruit. Out of curiosity, I parked the car and walked a few of the rows. What immediately caught my eye was that the fruit zone – usually confined to a few feet in height around waist-level – was from below my knees to above my head. What was even more remarkable was the fruits’s quality: never before had I seen such tiny berries, on such tiny clusters. This was the kind of fruit that any winemaker dreams of working with, and that seems to elude us no matter how hard we try to farm for it.

| I started making some calls and tracked down my neighbors who own the vineyard: Doug and Victoria King. I met Doug and Vickie on a cool summer day at their home, and they explained the vineyard’s history. They planted it in 2009, on advice from David Addamo, a nearby vintner and neighbor who just a year or so later went bankrupt and left the area. The following owner of the Addamo property, Randeep Grewald, made a deal with the Kings to continue farming it – for a fee, of course – and then to purchase the fruit after each harvest. “The problem was,” explained Doug, “I lost money on it every year.” Then came 2020, and Grewald stiffed the Kings for all of the fruit that the vineyard produced that year.

Doug is a savvy businessman, and finally he had had enough. “I just turned off the water and called it quits,” he said. “I wasn’t going top spend another dollar on it.” So for an entire year, it received no care whatsoever: no fertilizer, no spraying, and most remarkably, no water.” I made a deal with Doug to harvest the fruit (lucky me!), and to lease the property and take over vineyard management for the years to come. So by complete happenstance, this new vineyard leap-frogged our new planting to become Lumen’s first estate vineyard. Was wild a good thing? It certainly was in 2021. But what about 2022 and the years beyond? Stay tuned for the rest of the story. Up next? The Coming of Randall. – Will Henry |

Some of the greatest discoveries of mankind were made by accident.

Perhaps the best known (and beneficial) was made by scientist Dr. Alexander Fleming, who went on vacation for a few weeks and returned to see that his petri dishes had overgrown with mold. His discovery: penicillin. Other examples of benign errors include potato chips, plastic, Play-Doh and, drumroll… Viagra. I wanted to say something cute about wine and viagra, but think I will just leave that one alone.

Lane Tanner has been making wine for forty years, but she just might have made a discovery recently that will highlight her career. It all started a number of years back, when she was throwing a dinner party and making Thai food. At the end of the evening she had a heap of leftover ginger and didn’t know what to do with it. As Lane is a notorious miser, she wanted to figure out a way to preserve the ginger to use at a later date, but freezing it never seemed to work. She had an unfinished bottle of Chardonnay on the counter (also from the party), so she grabbed a container, dropped the ginger inside, and covered it with wine. Into the fridge it went, and slowly moved its way backward behind other items as the months went by.

A year later, Lane was cleaning out the fridge and was surprised to rediscover the container. Out of curiosity (something Lane is never short on), she opened it up and poured out the wine into a glass. Remarkably, the wine, now with a hint of ginger, was a fresh as the day that the cork was pulled.

The antioxidant properties of ginger root have long been known, but until this day, no one had thought to use it in wine to prevent oxidation. Perhaps, thought Lane and I, it could be used in place of sulfites to make a so-called ‘natural’ wine? In 2019 Lane we launched our first experiment and made a single keg of wine later dubbed ‘The OG,’ after Orange-Ginger, which was a skin-contact Pinot Gris combined with ginger-infused Grenache Blanc. The experiment was a whopping success. The OG is still tasting fresh and beautiful to this day.

The following year, Hey Ginger Chardonnay was born. We are now proud to release our second vintage of this fascinating wine, which only has three ingredients: Chardonnay grapes, fresh ginger, and yeast. The Chardonnay is sourced from old vines in the Goodchild Vineyard in the Santa Maria Valley and picked at low sugar (and high acidity), giving it even more stability in the bottle. We macerate the fresh ginger and place it into giant tea bags, which is then dropped into the tank of wine during fermentation. The result? Think Chablis with a slice of ginger. And let me tell you, there is no better accompaniment to Asian cuisine.

This year I finally got up the guts to submit the wine for critical review. I was worried that the wine establishment would balk at anything but grapes going into a precious bottle of vino. I sent samples to the Wine Enthusiast, albeit with an explanation of our technique, and waited a few months to receive our review. Much to my delight, it was awarded 90 points and Editor’s Choice. Bravo! Let the ginger revolution begin!

We are offering Hey Ginger Chardonnay at only $25 per bottle for the next two weeks. Get some while you can. And better yet, build your order to six bottles or more – of any Lumen wines – and we will spring for the shipping.

– Will Henry

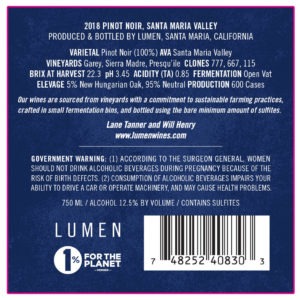

There’s a lot of geeky stuff on the back of a Lumen bottle – wine-geeky stuff. So why is it there? Not only are the basic facts listed – vineyard source, AVA, variety, clone – but also we share the pH, TA (titratable acidity), and Brix at harvest.

What, you may ask, is the significance of all that techie mumbo-jumbo?

All three of these data points help a winemaker see what kind of balance the fruit has, and ultimately, what balance the finished wine will be. This can mean the difference between a wine that tastes flabby (too little acid), to one that tastes too jammy (overripe, often which comes with flabby), or one that tastes too bitter or green (sugar too low and/or acidity too high).

pH and TA are both measurements of acidity. Think back to chemistry class and you will remember pH – it is a general measurement of acid vs. base balance in an aqueous liquid. pH of 7 is balanced – neither acidic nor basic. Grape juice (and hence wine) is generally in the 3 range – 3.2 being more acidic than 3.8. Generally speaking, the earlier you pick in the growing season, the lower the pH (and higher the acidity). TA is yet another way to measure acidity, and it can sometimes paint a more complete picture than just the pH alone. The TA basically gives a measure of the quantity of total acids in solution, while pH is simply a measure of their strength.

The brix at harvest is perhaps the most important measurement of all. Brix tells us the sugar content of the grapes in percentage of solution. Hence, 23 degrees brix means 23% sugar. Winemakers and winegrowers talk all the time about brix.

“So what is your vineyard at right now?”

“We seem to be stuck at 21 brix, but maybe after the heat wave this weekend it will shoot up a point or two.”

Then after two consecutive hot days, “Brix went up two degrees over the weekend. We are trying to get a crew in to pick pronto. But everyone wants to pick at the same time!”

This last conversation details one of the great challenges of making great wine. Nailing the pick day. As sugars increase in the grapes, acid decreases. A good winemaker will watch that balance closely as the grapes ripen, and then pounce when they see that moment of perfect balance. For Lumen, that happens when the brix is between 21 and 24, pH from 3.4 to 3.8, and TA of .5 to .8 grams per 100ml. But those are broad ranges, and the way that they interact tells a much more interesting story. For example, a wine that was picked at 3.4 pH and 22 brix with a TA of .8 would have, in my book, almost perfect numbers. It would be a wine worthy of aging, and should also be pretty damn good in its youth. A wine picked at 24 brix with .5 TA and 3.8 pH, however, is most likely going to be better in its youth, and not as age-worthy.

Some years are better than others, too. In the absence of large weather-related issues (i.e. heat waves, hail storms during growing season), vintage variation is largely due to subtle day-to day differences over the entire season. Cool years generally produce grapes with a higher acidity relative to sugar – which is why we like them so much. They may not be the best for number of beach days, but we will take the fog for better Pinot. My favorite kind of year (and this is not the same for all winemakers, mind you) is when I can pick my grapes at 22-23 brix and the acidity is still very high. That doesn’t always happen, though.

The other factor that greatly influences when we decide to pick is taste. Every single sample of juice, after it goes through chemical analysis, is then tasted by Lane and myself. That, more than anything else, is the deciding factor in choosing a pick day. The juice could be measuring 22 brix and 3.5 pH (which would indicate maturity), but the juice still doesn’t taste right. Maybe it’s still green and vegetal tasting, or maybe the fruit flavors just haven’t developed enough. In that case, we would have to make a tough choice to either let it ripen a little further, or pick before the acidity droops even further. It’s a touchy game.

Lane and I like to find the balance in grapes before making a wine from it. Well-balanced fruit means that we don’t have to mess with the wine at all – just ferment it, put it in barrel, filter it, add a teensy amount of sulfites and bottle it. Good fruit leads to wine with less additives, and more often than not, wine that will age longer and more gracefully.

Finding the balance, aging longer and more gracefully – isn’t that what we all want to find – not only in wine – but in life?

In this episode of Wine For Normal People, Will Henry of Lumen Wines shares his insights on organic and regenerative vineyard management. He discusses how these sustainable practices are integral to the health of the vineyard and the quality of Lumen’s wines. Tune in to explore the connection between the land and the wine in this thoughtful conversation.